Once Saved, Always Saved?

In this series on inviting the act of faith and what Catholics can learn from Evangelicals on the subject, I want to take a look at a common Evangelical doctrine that is often referenced in conjunction with the invitation to faith. This is the "once saved, always saved" doctrine. In short, this doctrine says that once one has made the act of faith, once one has given their life to Christ and accepted him as savior, one's status as "saved" can never be lost. When you receive the atonement for sin that comes through the Cross, this atonement is for all past and future sin in our lives. As one preacher says about the gift of salvation (paraphrased), "You didn't do anything to earn it, and you can't do anything to lose it." This gift having been received, God desires and works in the believing Christian to sanctify him in his conduct, to "bring his conduct up to the level of his calling." But should a believer resist this sanctification and persist in their sinful conduct, the result is not the loss of salvation but rather a "saved soul, but wasted life."

Before offering a Catholic critique of this Evangelical doctrine, I first want to highlight one strength, and that is the emphasis that it places on the centrality of Christ's actions as the cause of our salvation. This is something that I believe is not adequately emphasized in most Catholic contexts even though it is fully part of Catholic teaching. In my previous post, I referenced paragraph 1992 in the Catechism which states that "Justification has been merited for us by the Passion of Christ who offered himself on the cross as a living victim, holy and pleasing to God, and whose blood has become the instrument of atonement for the sins of all men." As Catholics, we need to reclaim a manner of presenting our faith that emphasizes total dependence on Christ for salvation.

ST. PAUL'S UNCERTAINTY

The Evangelical doctrine of "once saved, always saved" seeks to impart a certainty of salvation in the believer. St. Paul often speaks with a boldness about the sufficiency of faith, and I have already affirmed the value and legitimacy of the assurance that comes through faith. But there are also two passages where Paul speaks with an almost surprising sense of uncertainty about one's status before God.

This first is, in fact, a personal statement that Paul makes about himself.

Thus should one regard us: as servants of Christ and stewards of the mysteries of God. Now it is of course required of stewards that they be found trustworthy. It does not concern me in the least that I be judged by you or any human tribunal; I do not even pass judgment on myself; I am not conscious of anything against me, but I do not thereby stand acquitted; the one who judges me is the Lord. (1 Corinthians 4:1-4)

What I would like to emphasize here is that Paul draws a distinction between one's self-awareness and one's actual status before God. Like a master-psychologist, Paul is very aware of the depths of self-deception that we are capable of as human beings, to the extent that he insists on remaining open to the possibility that he himself is guilty of the same kind of self-deception.

Does this mean then that we must always remain skeptical of ourselves, living in a constant state of anxiety about the state of our soul? A second passage from Paul protects us from this kind of anxiety.

It is not that I have already taken hold of it or have already attained perfect maturity, but I continue my pursuit in hope that I may possess it, since I have indeed been taken possession of by Christ [Jesus]. Brothers, I for my part do not consider myself to have taken possession. Just one thing: forgetting what lies behind but straining forward to what lies ahead, I continue my pursuit toward the goal, the prize of God’s upward calling, in Christ Jesus. Let us, then, who are “perfectly mature” adopt this attitude. And if you have a different attitude, this too God will reveal to you. Only, with regard to what we have attained, continue on the same course. (Philippians 3:12-16)

Here again we see Paul identifying the very real possibility that we can remain hidden from ourselves. "Adopt this attitude" Paul says - in whatever measure it is in you to decide, decide to adopt this attitude. But Paul says that despite this, there may remain in you attitudes contrary to Christ. If there are, you can be confident that this too God will reveal to you."

There is no need, therefore, for anxiety. It is good, on occasion, to survey myself to determine if I am "conscious of anything against me." If not, then it may be that there is still something in need of purifying, but I can be at peace trusting that "this too God will reveal."

THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM

These passages from St. Paul don't provide any conclusive argument against the "once saved, always saved" doctrine, but they do point us to the heart of the issue. The central problem with this doctrine lies with the fact that we are not the kind of creatures who are capable of committing our whole selves all in one decision. Faith is, after all, a commitment of our whole selves to Christ. But to commit our whole selves, we must be in possession of our whole selves. St. Paul's insights above illuminate for us the fact that there are parts of us that remain a mystery to us, areas of our life in which we lack freedom and that make us incapable of committing that part of our selves to Christ.

Let's speak plainly of the experience of every Christian. Those who embark on the Christian journey with sincerity inevitably experience what Paul speaks of in the Philippians passage above - God reveals to them, over time, some "different attitudes" that they hold, some area of their life they need to surrender over to God. It may be their marriage, their finances, their work, or just a particular way of acting towards others. I believe most Christians who experience this think to themselves something like, "How could I have been blind to this for so long?" The reality is that God's grace is working in them a new freedom. They had previously been in bondage in this area of life, but the grace of God is releasing them and restoring their freedom.

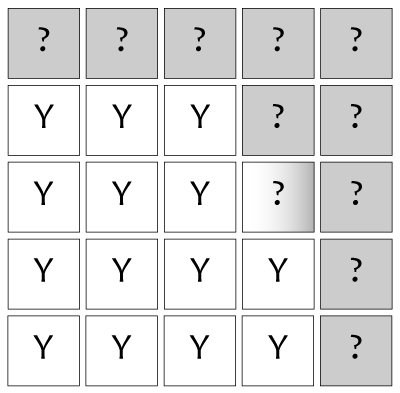

The image below helps me illustrate this notion. The grid represents the individual, the person, with each block representing a different aspect of their life.

The white boxes are those are of life where the person has freedom and self-possession. The gray boxes represent a lack of freedom in a particular area of life. Since we are talking about someone who is committed to the Lord, the white boxes have a "Y" for "Yes" in them - this is someone who is completely committed to Christ insofar as they are capable. But the gray boxes have a "?" because these are areas where the person lacks freedom. Where there is no freedom, there can be neither a Yes nor a No.

Now the grace of God works in us to increase our freedom, to reclaim lost territory in our hearts. And as this freedom is reclaimed, the question mark emerges from the shadow and demands an answer - "Will you give this area of your life to Christ as well?"

In the normal course of things, we would expect this ? to turn into a Yes. But if freedom is to be freedom, if choices truly are choices, we have to admit the possibility that with this newly unlocked capacity for freedom there is the real possibility that the person will use this new freedom to reject Christ.

GIVE IT ALL YOU GOT

The main point of this illustration is to demonstrate the reality that we are not the kind of creatures who are capable of committing our entire selves in a single decision. Does this then make it wrong to invite people to "commit their lives to Christ"? Not at all. The beautiful thing is that God's justifying action does not wait for us to be capable of that full and completely free commitment. The act of faith that God asks from us is the total giving of that part of the self that one has the capacity to give. Whatever other freedoms may be lacking, the decision to commit to Christ, with whatever measure of freedom one possesses, lays the foundation for all other decisions. It is the North Star, so to speak - it is a decision that wraps all other decisions within itself, if not yet in reality then by intention.

An analogy with marriage is fitting here. At the moment of saying "I do," bride and groom make a lifelong commitment to each other, a total gift of self. They are saying to each other, "I am committing myself to this marriage with all its implications, even if I cannot fully know what those implications are." The commitment is real and is meant to guide all future decisions, but future decisions themselves also constitute genuine decisions, new moments in which they can either ratify the initial decision or back out on the commitment.

And so the commitment to Christ is a real and important commitment to make. It is the pledge of salvation. It is a genuine assurance for it lays claim, so to speak, to God's faithfulness and implicitly invites Him to reveal any "different attitudes" we may be carrying unawares.

DON'T JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER

A second reason that it is so important to invite this act of faith is because we cannot outwardly discern anyone's level of freedom. The core decision to accept Christ, to commit one's life to him, can be sincere and effective even while significant areas of life where freedom is lacking remain "unredeemed" or objectively disordered. God does not wait for us to clean up our lives, to learn all the Commandments and obey them thoroughly before inviting us into relationship with Him. In fact, that relationship is essential, the necessary precondition to our being able to conform our conduct to His calling.

These words from George MacDonald express this reality beautifully:

God regards men not as they are merely, but as they shall be; not as they shall be merely, but as they are now growing, or capable of growing, toward that image after which He made them that they might grow to it. Therefore a thousand stages, each in itself all but valueless, are of inestimable worth as the necessary and connected gradations of an infinite progress. A condition which of declension would indicate a devil, may of growth indicate a saint.

This post is the third in a series on “Inviting the Act of Faith.” The full series can be accessed below:

Part One: Inviting the Act of Faith: Introduction

Part Two: Faith, the Pledge of Salvation

Part Three: Once Saved, Always Saved?

Part Four: Faith and Encounter

Part Five: Going “All In” with God

Part Six: What Does Rescue Look Like?

Part Seven: A Major Lacuna in Catholic Ministry

Part Eight: Practical Ways to Invite Faith